Once you know what to look for, there are signs of recovery everywhere. Today’s episode of If I Speak… had a letter writer with a porn-addicted boyfriend (a genre of dilemma that also comes up on The Receipts). Someone talking about HP? That’s their Higher Power, or God as they understand what that to be to make the Twelve Steps work for them. And all that talk of ‘surrender’ alongside cortisol and rest on that skincare-wellness influencer girlie on your grid? That’s a faith-based concept, that’s trickled out from fellowships and into the contemporary self-care, slow down lexicon. I resent it less than ‘divine feminine,’ a slogan which can be found on this year’s (tedious) Bella Freud x Marks and Spencers collaboration jumper, and indeed the broader concepts of masculine vs feminine energy.

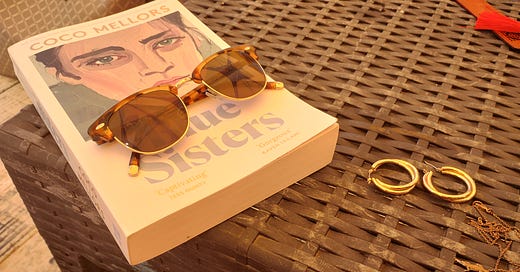

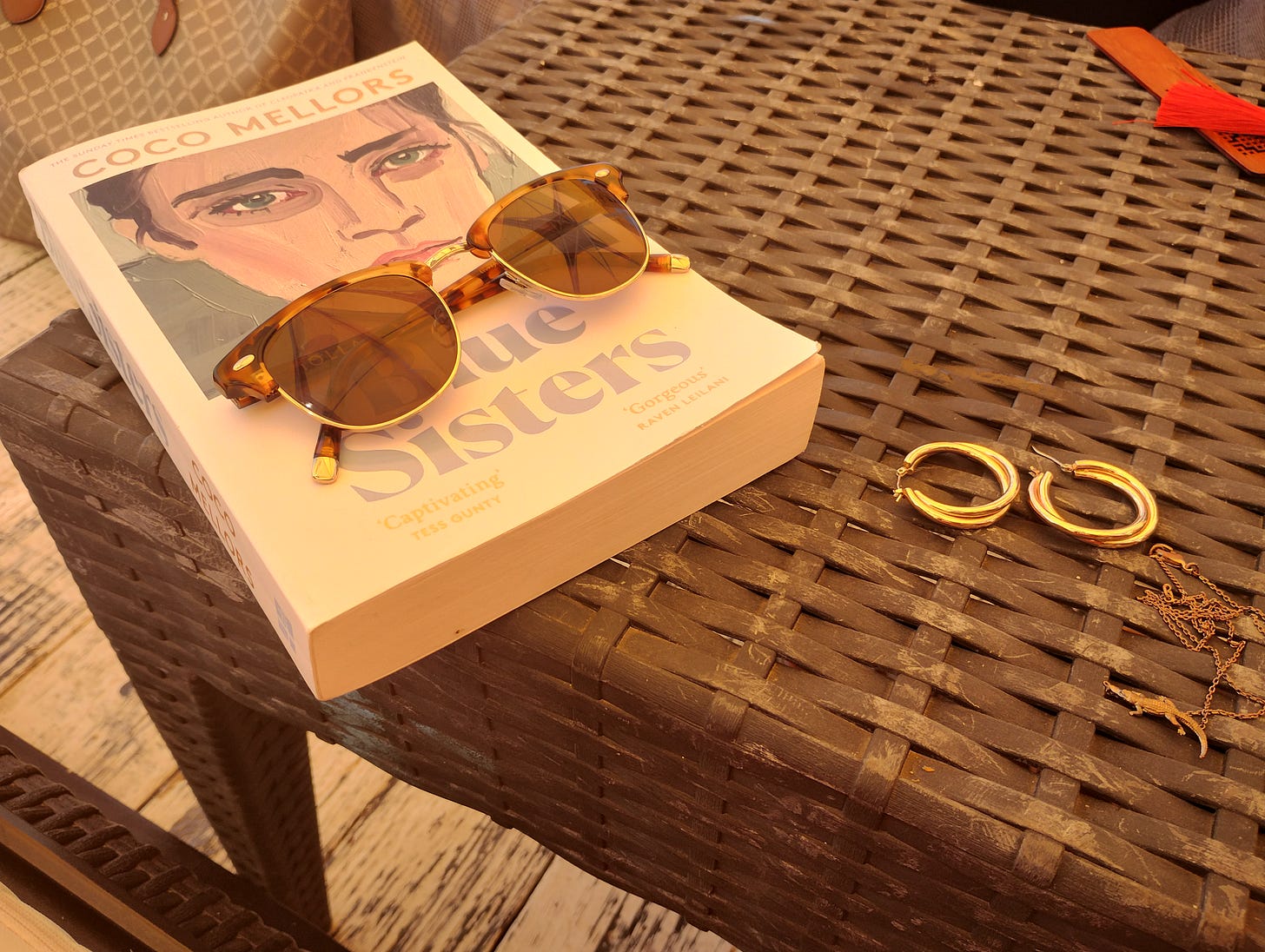

Recovery is also in literature. Specifically in the work of Coco Mellors, the British-American author of two novels, Cleopatra and Frankenstein and this year’s release Blue Sisters. I picked up the latter at the WH Smith’s at Gatwick as I love an airport paperback: generally, they are trade size softbacks released the same time as the hardback, but only a selected number of releases get them. I got Mellors’ book and Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time on buy one, get one half price.

Mellors got sober during the writing of her first novel, aged 26, and the themes of alcoholism and addiction more generally are found in both books. I’ve only read Blue Sisters, which tells the story of the four sisters of the Blue family: Avery, Bonnie, Nicky and Lucky, each with their own relationship to compulsive behaviours. They live between New York, London, Paris and LA. They model, lawyer, box and teach. They are addicted to alcohol, uppers, opioids and pain; each is seeking her own version of oblivion.

Four sisters…and a very blonde author. But fear not! this is a Little Women/Pride & Prejudice of a post-2020 reading list age. The sisters that are alive aren’t just into WASPs like themselves: there is an Indian wife and a man described as ‘young, Black, and striking, though not exactly handsome,’ whose presence in the lawyer’s life reveals how sobriety can be upended in a multitude of ways. He is a poet from Zadie Smith country (Willesden Green) but I’ll come back to him later. In LA, there is a ‘British expat’ Peachy, who is described immediately upon entering the narrative as ‘the son of a Congolese mother and white English father who had sent him to Eton at the age of eleven, then promptly divorced each other never to speak again.’

The description, and the fact it was dumped in the text like that, in a manner more in keeping with YA and genre fiction than literary, reminded me of the function of doting husband Patrick in Sorrow and Bliss, a book I found to be cynical and cowardly with regards to the madness of madness. Patrick and Peachy both are ethnic boarding school boys from broken homes — it’s as though the authors want to make it clear they are aware that people are more than just how they might shallowly appear or be stereotyped as, which is a worthy point to make, of course. But as a trope it’s as didactic as the thing it’s trying to avoid, mainly because you get the real sense someone like Mellors probably doesn’t know many non-white people who don’t come from money, so in a way it’s more comfortable to write about them than a white kid who went to a comprehensive school outside a desirable catchment area.

There are also Accents in the book. In a way that surprised me, but perhaps it’s more acceptable in American literature than it is this side of the Pond? Pavel, the Russian boxing trainer, has his speech typed out in a curiously old fashioned way. To be honest, it borders on the ‘in Soviet Russia, box ring you’ meme. The Blue sisters don’t have their cadences rendered in this way. Because they don’t have accents; they have voices. Similarly, another sister encounters a live authentic Londoner on her journey back to retrieve some lost property from a club. The dancer says “Can I ‘elp you?” in a way that’s more Mary Poppins than contemporary slice-of-life.

In a sense, Blue Sisters feels like a repudiation of some of the more recent narratives that have focused on female friendship and chosen family. Sisterhood is described in the book’s opening, as blood and flesh, and time shared in the same womb. It’s both nature and nurture, which are at the heart of the maladaptive patterns and emotional dysregulation that can be precursors for addiction. As trauma has become more mainstream as a concept, it makes sense that we might be increasingly drawn to genealogy and also addiction. The addiction framework extends to all kinds of social life beyond the traditional vices of alcohol, gambling and drugs: overeating, overspending, love…all can be entry points to a journey of self-knowledge, marked by an honest, neither self-flagellating nor minimising inventory for one’s past misdeeds so you can be forgiven and understand yourself as a lovable and fallible mortal, if the Twelve Steps are what you go by. And yes, that journey is a Christian one in origin, by the way — which is why I find the appeals to ‘surrender’ in what some might think of as spiritual woo woo spaces kind of amusing. In a sense, it’s an absorbing, immersive read.

In another sense, it’s fundamentally a bit naff. When I read the ending — spoiler but there’s parakeets and Hampstead Heath which made me text my friend that Mellors was doing ‘Richard Curtis but for the Reformation girlies’ (clothing brand Reformation subsequently launched a book club/talk event series hosted by Pandora Sykes called ‘ref reads’ — and Blue Sisters was one of the picks…) — I did have a frustration at the neatness of it. It spoke of a writer who was at times good, but not yet able to challenge herself or her audience.

When I went onto her instagram after the controversy of her basing her black poet character on a real black London artist who calls his work ‘party poetry’ (in the book, the lawyer sister Blue coins the term herself to put on the guy’s work spontaneously in conversation), I noticed that in one recent caption, she spoke of being happy to be wearing red after months of blue outfits. ‘New season, new book to work on, new colours to wear. Not done with blue for good (never! after all, there’s always the paperback tour)…’ I felt sad. Is this what it takes to get two bestselling novels in a post-pandemic age? Colour coordinate your outfits for six months straight with the on-the-nose title of your book? Be as photogenic as Coco to land the 4th Estate marketing campaign of dreams? Whatever happened to writing the best sentences you can muster? Imagine if she’d spent, and was editorially encouraged and incentivised to spend, more time honing the characters. I suspect the James Massiah/'Charlie' debacle could have been easily avoided.

Which is interesting because you get whiffs that Mellors might be a bit of a book snob. There’s a cache to writing literary fiction; I think the team behind the book want it to be, at the very least, a thinking woman’s beach read. An incidental character we aren’t supposed to consider much of a thinker has a pile of books on their bedside, including titles like Sapiens and The Power of Now. I don’t always think the narrator of a book holds the same moral framework as the author, but in this case, I do, because, despite the head-swapping between the three sisters, it feels as though she has split herself into each of them to varying degrees.

The result in the text are a number of ‘nearly, but not quite’ passages. Consider:

She used to love meetings, love the stories, the depth of identification that could bubble up from nowhere like a hot spring in a desert. She could be listening to someone ostensibly nothing like her who would describe, with almost uncanny precision, her exact feelings and thoughts. That was the magic of fellowship, when it worked: the realization that the parts of yourself that were the most hidden, most shameful, were what connected you most deeply to others. In AA, you were never an outsider, never alone. For years it had felt like she always had a golden lattice of sober people beneath and around her, ready to catch her if she fell. But she had been falling for a year now, and no one had caught her yet.

You start off with good faith, then the clang of ‘hot spring in a desert’ makes your bad writing antennae prick up. But what is being written about, so plainly and clearly, has a truth to it — is fellowship a bit like what it’s like when you read a character a feeling something you’d never spoken to anyone about experiencing? — that you chide yourself for your churlishness about the word choice. But then, damn it, again, ‘ a golden lattice of sober people’? Ah, would you catch yourself on. Nevertheless, it is sad if no one has caught her yet and she’s still falling.

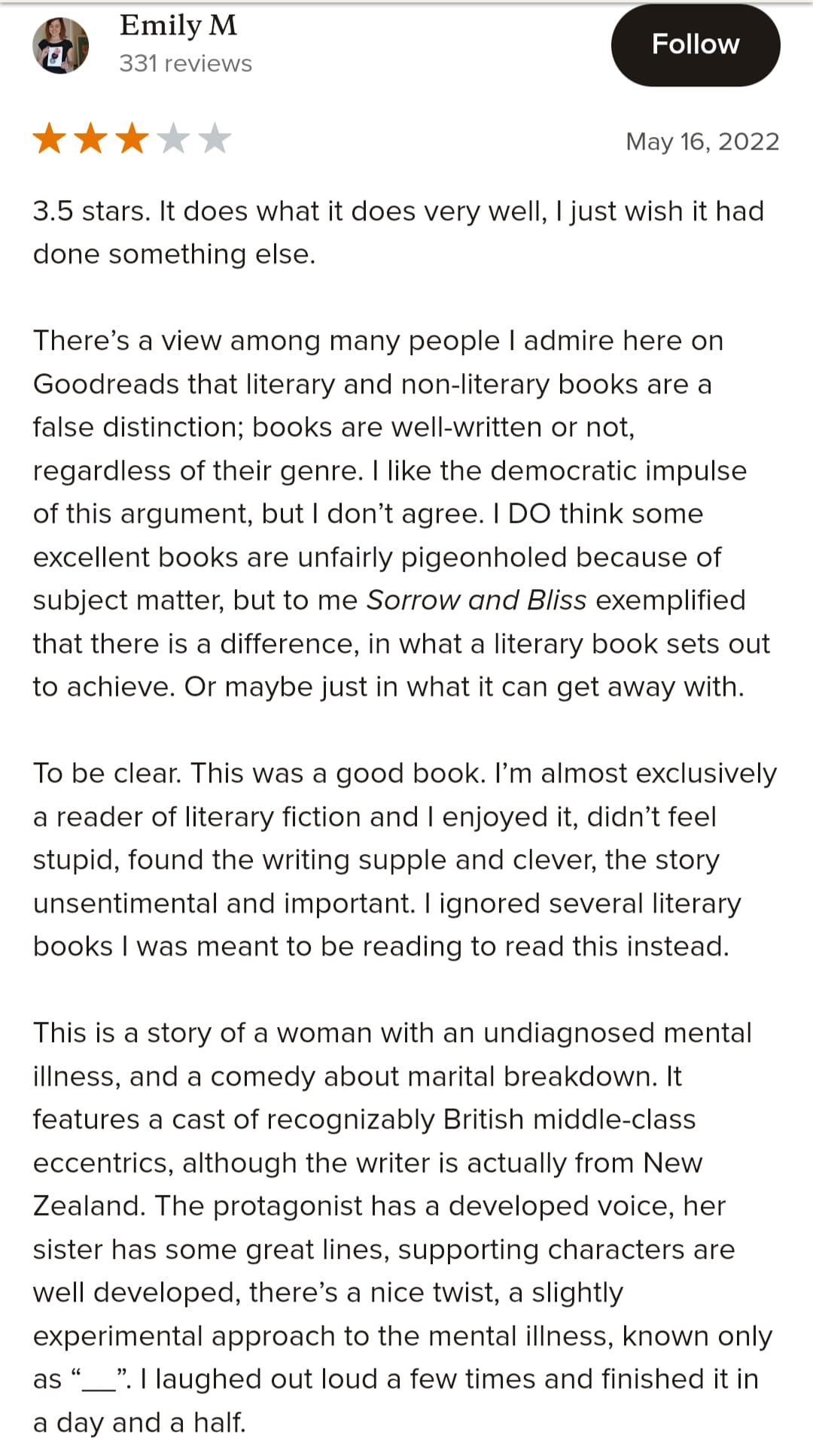

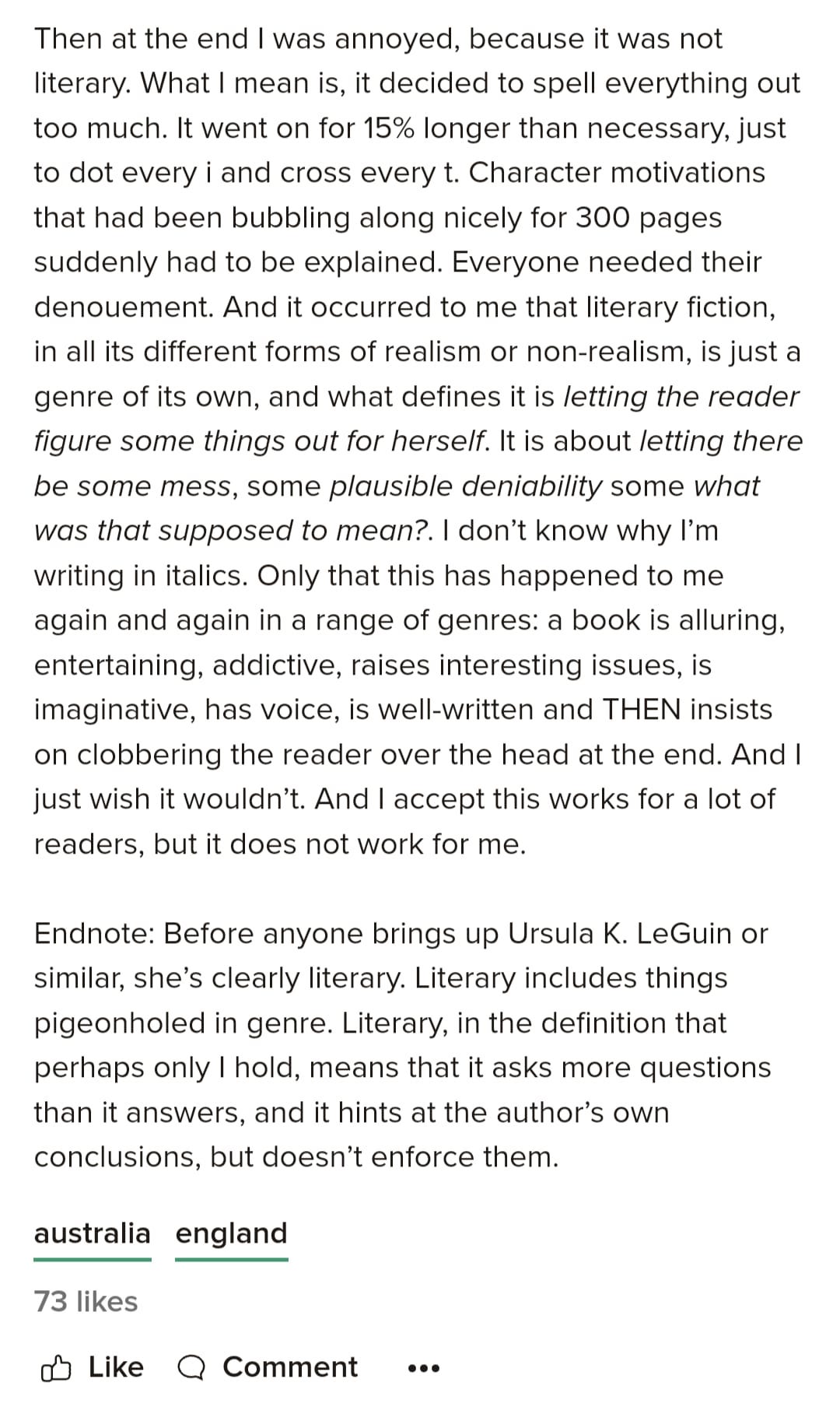

Does the distinction between literary fiction and commercial literary fiction (or uplit, or book club or whatever it is) really matter? I don’t know. I think it’s the lack of time in the ovens with the drafts that seems to be the real bother, and the TV rights bidding wars. But I’ll end tonight’s edition with a Goodreads review of Sorrow and Bliss that I came back to when chatting about Blue Sisters to a friend back in June:

Oh that’s a great definition of literary!